We’ve all seen them: the athletes who defy the clock. Maybe it’s the 65-year-old on your local trail, running past people half her age, or the 50-year-old cyclist who just broke his personal record on a local segment he first tackled as a student. They look like they’ve found a secret formula, or perhaps they’re simply genetic outliers, untouchable by the steady, inevitable march of time.

You might wonder, what’s their secret? How can they keep going? Every athlete with a few years under their belt (and especially anyone starting later in life) has had the same nagging thought: “Am I already past my peak?” For endurance athletes, such as marathoners and cyclists, that doubt often surfaces after a breakthrough race, making you wonder, “Was that it? Is it all downhill from here?” For the late starters among us, the worry is different: “Is it too late to start this journey and see real progress?”

This line of questioning is natural, but it’s rooted in a misconception: the idea that your endurance career has a fixed expiration date. In reality, reaching your personal peak often takes far longer than we assume, which means your ‘best year’ might still be waiting for you further down the road. The science offers a far more hopeful—and realistic—perspective: by looking at the data from masters athletes in their 40s, 50s, and beyond, we can see that the climb toward our full potential is a long, rewarding arc, proving that human capacity is significantly more durable than most people think.

Why This Question Matters: The Endurance Journey Mindset

How long can you really keep improving your endurance? Well, that really comes down to how you look at it. Rather than viewing your performance as a single mountain top, it is vital to see it as a vast arc, spanning decades. Where you land on that arc (and what the final descent is like) is not pre-determined by anything on your birth certificate.

Instead, your performance, and your potential for continued improvement, are shaped by three key variables—two of which (you’ll be happy to know) you can absolutely control:

- Genetics (The Hand You’re Dealt): This sets your initial ceiling, influencing your baseline VO₂ max (the maximum amount of oxygen your body can utilize during exercise), your muscle fiber composition, and your body’s inherent response to training. You can’t change this, but you rarely train close enough to this genetic ceiling for it to matter much until later in life.

- Training History and Volume (The Work You Do): This is the most significant lever. The accumulated stress and adaptation from your training over months and years build your engine. As we’ll see, high volume and consistency aren’t just for fast times today; they stack the odds in your favor against age-related decline tomorrow.

- Age-Related Changes (The Curve): This involves fundamental physiological changes, such as a decline in maximum heart rate (HR max) and reduced elasticity in your heart and arteries. But here’s the crucial insight: endurance training can dramatically change the slope of this decline.

So, let’s dive into what the research says about each era of your life and your training (whether you start in your twenties, your fifties or beyond).

Those First Years: How Fast Can You Improve at the Beginning?

If you are a new athlete, a late starter, or someone returning to structured training after a long break, here is the most exciting piece of scientific reassurance: The early part of your endurance journey is steep, and you can achieve substantial gains quickly.

During your first three to five years of consistent, structured training, your body is highly sensitive to new stimuli, and the resulting performance gains can be significant. This happens because you are rapidly closing the gap between your current fitness level and your genetic potential.

The Power of Initial Adaptations: Your VO₂ max Surge

The primary metric driving early endurance improvement is a rapid increase in VO₂ max. Let’s look at strong evidence from meta-analyses showing that the body is highly responsive to training, regardless of starting age.

- Significant Gains in Older Adults: For instance, a meta-analysis by Huang et al. (2005) specifically examining older adults found that structured endurance training yields substantial increases in VO₂ max. This underscores the fact that your body retains its plasticity (its ability to adapt and improve) well into your 50s, 60s, and beyond. Of course, if the gains are significant for older adults, they are often even more pronounced for younger, less-trained individuals.

- The HIIT Advantage: To maximize these early gains, the research points toward intensity. A systematic review by Milanović et al. (2015) analyzed controlled trials and concluded that High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) is generally more effective than Continuous Endurance Training (CET) for improving VO₂ max in adults, including recreationally active and moderately trained individuals. Your takeaway? Structuring high-intensity work into your early training phases is a powerful, evidence-based strategy to jump-start your cardiovascular engine. If you’re a runner, this means incorporating interval training and speed work into your training.

The key idea here is that the foundation—the cardiovascular system, the mitochondria in your muscle cells, and your ability to tolerate volume—is laid down in those first few years. So, remember that the early journey is steep, and you improve a lot because you’re relatively far from your personal fitness ceiling. This rapid progress is one of the most motivating phases of the endurance journey, setting the stage for the long-term consistency needed in the decades that follow. A word of caution, however: too much intensity too soon can easily lead to injury and overtraining.

The ‘Building Decade’: 5-10+ Years of Structured Endurance Training

If the first few years are about rapid adaptation, the period that follows (the ‘building decade’)is about consolidation and refinement. For many endurance athletes, performance and VO₂ max can continue to improve over a decade or more of structured, progressive training.

This phase is where the work you put in truly stacks up, often allowing elite athletes to hit their personal peak performance in their late 30s or even early 40s in certain long-distance events.

Slowing Down the Curve, Not Stopping the Gains

In this phase, you encounter the concept of diminishing returns: the huge leaps in VO₂ max seen in the first few years slow down significantly. However, improvements don’t stop; they become more nuanced and reliant on experience.

Data from longitudinal studies of highly trained athletes help us understand the immense physiological reserve you build during this decade. The classic studies by Rogers et al. (1990) and Trappe et al. (1996), which followed endurance runners for many years, are often cited to show that those who maintained a high level of training were able to dramatically slow the rate of decline in VO₂ max compared to less active peers.

This points to the power of the accumulated training load: you are not just improving your fitness year after year; you are strengthening your resilience against the future effects of aging.

undefined

Polar H10

Heart Rate Sensor

When it comes to accuracy and connectivity, Polar H10 heart rate sensor is the go-to choice. Monitor your heart rate with maximum precision and connect your heart rate to a great variety of training devices with Bluetooth® and ANT+.

Enjoying this article? Subscribe to Polar Journal and get notified when a new Polar Journal issue is out.

Subscribe

Race Performance: The Pillars of Progress (In Years 5–15+)

It’s easy to get caught up in the numbers and assume that once your VO₂ hits a plateau, your days of setting PBs are over. After all, if the size of the engine stops growing, how can the car go any faster?

The answer lies in the distinction between physiological capacity and race performance. While VO₂ provides the ceiling, your actual speed on race day is determined by how efficiently you use that oxygen. In this building decade, you transition from just building an engine to becoming a master mechanic of your own performance.

Once you are near your peak physiological potential, continued progress shifts toward three critical pillars: skill, efficiency, and optimization.

1. Accumulated Volume: The Efficiency of Miles

There is a specific kind of toughness that only comes from years of consistent movement. As you stack years of training, your body undergoes deep cellular changes:

- Metabolic Efficiency: Your muscles become better at burning fat as fuel and clearing lactate, allowing you to sustain a higher percentage of your VO₂ for more extended periods.

- Structural Resilience: Your tendons, ligaments, and bones become hardened to the stress of endurance, meaning you can handle higher intensity with less risk of injury.

2. Better Pacing and Race Craft: The Intelligence Factor

Performance is a skill, and experience is your greatest coach. A seasoned athlete often beats a fitter rival with less experience simply by knowing how to execute.

- Biofeedback: You learn exactly what your threshold feels like and how to sit right on that edge without crossing it too early.

- Execution: Knowing how your body reacts to heat, hills, and fueling allows you to execute a race with flawless pacing. In a marathon or a long trail race, perfect execution can save minutes that pure fitness cannot buy.

3. Refined Training: Precision Over Power

In your early years, almost any training works. In the building decade, you need a scalpel rather than a sledgehammer.

- Specific Optimization: You move away from generic plans and toward workouts tailored to your particular weaknesses—whether that’s uphill power for a trail runner or top-end speed for a marathoner.

- Advanced Periodization: You learn how to cycle your training so that you hit your absolute peak precisely on race day, using expertly managed tapers to arrive at the start line both fresh and fit.

The key idea is this: You can still be improving after 7–10 years of training, but progress becomes more about consistency, detail, and execution. Even if your VO₂ remains stable, your ability to utilize that engine grows. This decade provides the deep foundation that will help you flatten the decline curve in the years ahead.

Aging and Endurance: What Actually Happens with VO₂ max and performance?

This is the question every long-term athlete eventually asks. While aging creates an undeniable headwind, the science is clear: your training acts as a powerful counter-engine that keeps you moving forward for decades longer than most people expect. The physiological curve is predictable, but the slope is within your control.

The Endurance Arc: Performance vs. Aging

Endurance performance doesn't fall off a cliff; it follows a curvilinear path. According to research on masters world records (Lepers & Cattagni, 2018), performance is generally maintained until age 35, followed by a modest decline until 50. The more pronounced drop-off typically doesn't occur until after age 60 or 70.

The difference between a trained athlete and a sedentary person during this journey is staggering:

- The Sedentary Baseline: For untrained individuals, VO₂ max drops by roughly 5–10% per decade, accelerating after age 70.

The Athlete Advantage: Lifelong endurance athletes experience a significantly slower decline—often nearly half the rate of their sedentary peers—thanks to sustained training volume and intensity (Reaburn & Dascombe, 2008).

Why Training Flattens the Curve

While a decline in HR max is an inevitable part of aging, training protects almost everything else. By staying active, you maintain a higher maximal stroke volume (the amount of blood your heart pumps per beat). Training also preserves heart size, capillary density, and mitochondrial efficiency—factors that sedentary individuals lose rapidly.

Essentially, you enter your 40s, 50s, and 60s with a much higher fitness baseline. You aren't just faster than your peers; you are physiologically 'younger.'

The Late-Starter’s Edge: Plasticity at Any Age

If you are just starting in your 40s or 50s, the news is even better: your body remains remarkably responsive. While your absolute physiological ceiling might be lower than it was at age 25, your current VO₂ max is likely far below your new potential at this age.

The Reaburn & Dascombe (2008) study confirms that older cardiovascular and muscular systems retain significant plasticity. This means a late starter can still see substantial, double-digit percentage increases in VO₂ max through structured training. You get the powerful feeling of improving and getting faster, even if your PBs from two decades ago stay on the shelf.

Case in Point: A study of a world-record-holding masters runner (Lepers et al., 2018) showed that despite a gradual, age-related decline in VO₂ max, they maintained exceptional, elite-level performance into their 70s through disciplined training.

The bottom line is that aging changes the slope, but it doesn't remove the benefits of the work. Whether you’re maintaining a high peak or building a new one, the engine is still very much open for upgrades.

undefined

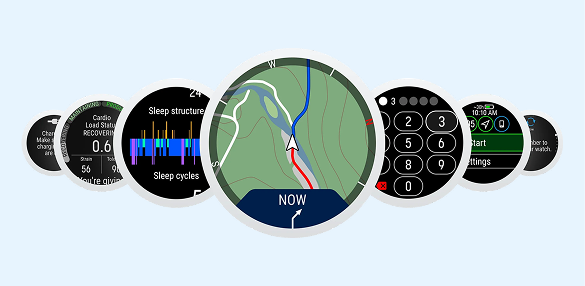

Polar Vantage M3

Smart Multi-Sport Watch

Polar Vantage M3 is a smart multi-sport watch for multi-sport athletes that’s compact yet powerful, stylish yet strong, and designed to bring extraordinary training, sleep and recovery tools into everyday life.

Can You Still Improve If You Start Late?

This is perhaps the most hopeful message in endurance science: Is it too late to start endurance training in midlife? Absolutely not!

Whether you’re starting your first running plan at 45 or tackling your first triathlon at 60, your body remains remarkably capable of adapting and improving. The ‘late starter’ athlete bypasses years of the slow, shallow decline experienced by their sedentary peers, leading to rapid and significant functional gains.

The Power of Midlife Intervention

The evidence from controlled trials and meta-analyses is overwhelming: older adults can still significantly improve VO₂ max and endurance performance with structured training over 6–12 months or more.

- A study from Valenzuela et al. (2020) reinforces the finding that the cardiovascular and muscular systems retain high plasticity well into older age. The high VO₂ max seen in masters athletes is, in part, a testament to the body’s ability to maintain training responsiveness.

- Reversing Cardiac Aging: Landmark interventional trials, such as the one led by Howden et al. (2017), showed that high-dose, supervised endurance training initiated in previously sedentary middle-aged adults (45–64 years) could significantly reverse age-related cardiac stiffening. By training consistently, participants improved left ventricular elasticity and increased maximal stroke volume, essentially showing that years of sedentary decline are modifiable. This powerful finding demonstrates that the physiological components that govern VO₂ max remain trainable.

Defining ‘Improvement’ for the Late Starter

When you start late, improvement might not mean beating your 20-year-old self (though early race times may drop quickly). Instead, ‘improvement’ takes on a positive, multi-faceted definition:

- Measurable Gains in Competition: For those who choose to test their progress when racing, this phase often yields consistent, clear drops in finish times. As your VO₂ max rapidly increases and your body adapts to the training load, your race performance becomes a tangible measurement of your engine’s growth.

- Slower-Than-Average Decline: Compared with your age-matched sedentary peers, your fitness curve will immediately flatten. By becoming active, you trade the steep, typical decline for the much shallower slope of the trained athlete.

- Improved Health, Economy, and Resilience: Even if your VO₂ max eventually plateaus, you gain critical health markers, including better exercise economy (less energy needed to maintain a pace), improved metabolic health, and enhanced overall resilience.

The key idea is that it’s absolutely worth starting, even at 40, 50, or later—the curve is different, but the scientific evidence shows that the outcome is still highly positive and life-changing.

How Long Can You Keep Chasing Personal Bests?

The PB window is often much wider than traditional wisdom suggests. While your absolute physiological ceiling will eventually lower, your ability to reach and sustain your current potential allows for a long, rewarding competitive arc.

A Nuanced View of Peak PerformanceYour timeline for chasing personal bests depends largely on your starting point:

- Early Starters (20s–30s): After the building decade, absolute PBs may keep improving for 10+ years before plateauing as you approach your genetic ceiling.

- Late Starters (40s and beyond): You can often expect 5 to 10+ years of clear improvement. Because you are starting further from your aged potential, you’ll see rapid gains that can lead to absolute PBs well into middle age.

- The Pivot Point: Eventually, age-related decline will outweigh training gains. When this happens, shifting your focus to Age-Group PBs or Best Performance for this Life Phase keeps motivation high and acknowledges the reality of your evolving physiology.

Flattening the Curve: The Qmax Strategy

To keep chasing your best for as long as possible, you must focus on the most trainable component of your endurance: Maximal Cardiac Output (Qmax). Research by Carrick-Ranson et al. (2023) shows that Qmax (the total volume of blood your heart can pump per minute) is the primary limiting factor as we age.

By flattening the curve of Qmax decline, you effectively delay the point where performance drops. You can optimize this preservation through:

- Sustained Volume: Maintaining a consistent aerobic base to preserve heart chamber size and stroke volume.

Strategic Intensity (HIIT): Including regular, structured high-intensity sessions to continue stressing the cardiovascular system. This high-end work is the most effective way to maintain the pumping power of the heart and keep functional markers high.Remember, you aren't just a passenger on a downward slide. By focusing on Qmax and shifting your goalposts to reflect your current life phase, you can keep the competitive fire burning for decades.

Shifting the Goalposts

The shift from absolute PB-chasing to best possible performance for this life phase is normal and incredibly motivating. Once absolute PBs become elusive, the focus shifts to:

- Age-Group PBs: Achieving your best possible time within your five-year age category. This is a competitive goal that keeps the training fire burning.

- Maintaining Functional Capacity: Ensuring your physiological metrics—your VO₂ max at age 65 or your performance at the lactate threshold—are as high as they can possibly be. As this comparative study from Vajda et al. (2022) confirms, the physiological benefits of lifelong running dramatically outweigh the risks for most people, ensuring a high quality of life.

Your endurance journey has more years than you think. As you can see, the evidence is solid: consistency and smart training help you delay that inevitable performance decline and keep competing fiercely for decades.

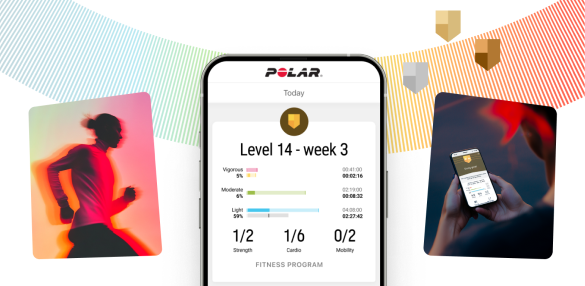

What to Do with This Information: Your Long-View Strategy

You now have the scientific blueprint for your multi-decade endurance training. The key shift is moving your focus from the weekly grind to the long-view strategy. You’re not just planning your next race; you’re planning your fitness in five-year blocks. Here’s how to apply this research to your training, using data to empower your decisions.

Your Strategy Stage One: Zoom Out and Analyze the Trends

Instead of getting hung up on a single bad workout or a temporary dip in race pace, zoom out and look at your endurance journey over years, not weeks. This requires tracking your data consistently, which is where we come in.

Use Polar Flow to analyze your performance and training load over multi-year periods. You’re looking for your long-term arc— the trends, not daily fluctuations. Here’s what to look for:

- VO₂ max Estimates: How has your estimated VO₂ max (or equivalent fitness metrics) changed over the last three to five years? If you are a lifelong athlete, the data should confirm the research: your decline should be shallow. If you are a late starter, look for the steep upward curve of your initial adaptation phase.

- Training Load: Are you maintaining the volume and intensity needed to flatten the curve? Remember the research: the single most significant factor determining the rate of decline in masters athletes is sustained training volume.

- Race Times: Plot your long-course race times over the years. Look for the predicted curvilinear decline (Lepers & Cattagni, 2018), which should confirm that your performance holds strong well past your expected ‘peak.’

Your Strategy Stage Two: Plan with Sustainability and Data

Use Polar’s data-driven insights to structure your training not just for speed, but for longevity and health.

- Plan Sustainable Cycles (1–3 Years): Commit to a training philosophy built around cycles of build, cutback, and recovery. Avoid the temptation to maintain peak volume year-round, which increases burnout and injury risk. This strategic periodization ensures your body gets the chance to solidify those hard-won physiological adaptations.

- Let Recovery Metrics Guide Decisions: The ability to recover effectively is the most fragile aspect of aging. Use Polar’s Training Load Pro and Nightly Recharge™ metrics to move beyond just following a calendar plan. If your body isn’t absorbing the training (low Nightly Recharge score), be realistic and modify the plan.

Your endurance journey isn’t just a race; it’s a marathon spanning decades. By using your data wisely, you take control of your performance arc and stack the odds in favor of a strong, healthy finish.

Your Endurance Journey Has More Years Than You Think

The science is clear, and thankfully, the message is undeniably hopeful: Your endurance journey is a marathon, not a sprint, and you have far more control over its length and quality than you might believe.

The common fear (that the best years are already behind you) is simply contradicted by science. We’ve seen that:

- You can improve for longer than most people assume—often a decade or more of steady gains, especially when focusing on consistency and smart training structure.

- Even when absolute PBs stop falling, the training still pays off massively by dramatically slowing the rate of VO₂ max decline and boosting your health and quality of life for decades to come.

- Starting later is not too late; it simply shifts the curve. The body remains highly adaptable, meaning significant functional gains are within reach, regardless of your starting age.

In short, your focus must shift from chasing your younger self to optimizing your current self.

Your challenge now is to pick a powerful, long-term goal—something that truly inspires you, like “strong and happy marathoner at 60” or “still crushing the toughest century ride at 75.” Use your data from Polar Flow and commit to good habits (consistency, strategic intensity, and prioritizing recovery) to get there.

The arc of your performance is long, beautiful, and ultimately, yours to shape. Get out there and make the next decade your best yet!

Polar Vantage M3

Polar Vantage M3

Polar Grit X2 Pro Titan

Polar Grit X2 Pro Titan

Polar Grit X2 Pro

Polar Grit X2 Pro

Polar Grit X2

New

Polar Grit X2

New

Polar Vantage V3

Polar Vantage V3

Polar Ignite 3

Polar Ignite 3

Polar Ignite 3 Braided Yarn

Polar Ignite 3 Braided Yarn

Polar Pacer Pro

Polar Pacer Pro

Polar Pacer

Polar Pacer

Polar Unite

Grit X Series

Vantage Series

Pacer Series

Ignite Series

Polar Unite

Grit X Series

Vantage Series

Pacer Series

Ignite Series