You step onto your treadmill, hit the quick-start button, and settle in for a gentle jog while watching your favorite show. It's a mundane, everyday part of modern life. But stop right there. That sleek machine under your feet has a history that is chaotic, dark, and utterly bizarre. Forget the notion that this invention was always about fitness; the origins of the treadmill are rooted in heavy industry, punishment, and even an attempt to stop a terrifying wave of heart disease that gripped America.

From ancient Roman engineering to the genesis of the home gym, the story of how the treadmill transformed from an instrument of torture into a life-saving medical tool (and now, a screen for watching your favorite shows) is one of the most unexpected and thrilling evolutions in fitness history. Join us as we trace the incredible, and often absurd, journey of the treadmill.

From Roman Crane to Victorian Torture

Let's begin in the 1st century A.D., when the Romans put the treadmill's earliest precursor to work: the treadwheel, or polyspaston. This was essentially a massive, human-powered crane wheel. Used instead of a traditional winch, men would walk continuously inside this large, hamster-like wheel to hoist heavy weights. The irony of using the original "wheel of misery" to build the empire that lasted a millennium is a tale only history could write.

The story gets much, much grimmer in the 19th century. If you thought your first day back at the gym was a brutal form of suffering, wait until you hear about the treadmill's truly darkest chapter, where it became one of the cruelest forms of punishment available.

Around 1817, an English engineer named William Cubbitt was asked by a friend—a Suffolk magistrate—to invent something to occupy the "idle prisoners" at Bury St Edmunds County Gaol. Cubbitt, a millwright by trade, took inspiration from that old treadwheel technology that had been used for centuries to drive mills and cranes.

However, he made two key changes that transformed the machine from a cumbersome tool into a genuine instrument of torture. First, he elongated the wheel, allowing more people to walk on it at once. Second, and crucially, he inverted it.

Instead of walking inside the wheel, prisoners were forced to tread on the outside steps. This meant treading became a climbing motion, vastly increasing the difficulty. To ensure maximum productivity (and maximum pain), Cubbitt covered the steps at the top of the wheel to keep prisoners at the level of the axel. This machine, ironically, bore less resemblance to a modern treadmill and more to a monstrous, multi-person StairMaster.

Cubbitt’s pitch was an insight into Victorian logic: the labor could grind grain or drive looms, teaching prisoners the "habits of industry." It was also easy to administer, required no training to climb, and provided a uniform punishment, with every prisoner forced to climb the same number of steps.

By 1824, this contraption of penal torture had spread to at least 54 prisons across Britain, and was popping up in Ireland, North America, and Australia. The literary legend Oscar Wilde even served his time upon its unforgiving steps. Prisoners were typically forced to walk for six hours daily, climbing up to 14,000 vertical feet, burning over 2,000 calories. One documented stint at Warwick Gaol saw prisoners climb the equivalent of the Empire State Building 13 times in 10 hours.

However, the power generated by all this suffering often went to waste. By the 1830s, industrial technology had advanced, and human labor was too expensive or simply unnecessary. Most treadmills ended up just pumping water around the prison, or at worst, "grinding air." The work was literally pointless, which, according to one academic, made it the "perfect punishment" for Victorian ideals of atonement through exhausting, useless toil.

Counter evidence of the harm—hernias, lung damage, even deaths from accidents—eventually led to the treadmill’s demise. It was finally abolished in 1902. With that final, grisly chapter closed, the machine was free to finally take a much stranger, and eventually much healthier, shape.

20th Century Developments

If you think your home gym’s motorized marvel is a product of late 20th-century genius, think again. Its story begins way back in 1911, when an inventor named Claude Lauraine Hagen filed a patent in the U.S. for a 'training-machine.' Now, this wasn't some clunky contraption—it was a piece of surprisingly detailed and forward-thinking equipment, especially if you consider that Olympic marathon runners were still using rat poison to enhance their performance only a few years earlier. The patent was granted in 1913, and Hagen’s design featured a treadmill belt and included a laundry list of modern amenities.

It's hard to imagine that in an era when a stiff walk was considered exercise, Hagen had the foresight to design his machine to fold up, allowing it to be easily transported. He wasn't done there; he added movable side rails to accommodate users of varying heights (a nice nod to universal design) and even took a shot at noise reduction. To avoid that horrible thump-thump-thump we all know, he attached four outer posts, essentially raising the belt off the ground. A brilliant side effect of this elevation? It allowed the incline to be adjusted. Whether Hagen ever turned this blueprint into a working, usable prototype is a question history hasn't answered—the evidence is stubbornly hard to come by. Yet, his genius survives: this patent is still cited to this very day in modern treadmill designs.

The decades that followed were less innovative. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, early models of the walking machine emerged, but these were manually operated. Forget the continuous rubber belt we glide on today; these required the user to actually push wooden slats with their own feet to create momentum. That’s right—if you wanted to walk, you had to power the entire thing yourself.

Enjoying this article? Subscribe to Polar Journal and get notified when a new Polar Journal issue is out.

Subscribe

Cardiac Stress Test

Meanwhile, America was undergoing a terrifying shift in public health. In the early 1900s, diseases like tuberculosis and pneumonia were the top killers. But by 1910, heart disease had surged into the number one spot, and it wasn't letting go. Cardiac failure, the most prolific killer in 1921, accounted for 13.6% of all fatalities. By 1940, that percentage had doubled. Public health officials were sounding the alarm: how do you prevent death by heart attack? You need a way to test the heart's health under stress.

The tool for the job already existed, sort of. In 1924, Dutch physician Willem Einthoven won the Nobel Prize for inventing the electrocardiogram (ECG). However, at the time, ECGs could only gauge extremes: a patient at rest, or a patient already in cardiac crisis, where the information would likely have come too late. An alternative, the Master’s two-step test (named after cardiologist Arthur M. Master in 1935), proved wildly unreliable, requiring patients to step on and off a small platform. Many found it too difficult even to complete.

What the medical field desperately needed was a machine that could gradually and accurately raise a patient’s heart rate with a steady, controllable workload.

As luck would have it, the treadmill itself was poised for a truly life-saving comeback. The 1920s fitness boom had already introduced numerous cycling and walking apparatuses designed to battle increasingly sedentary lifestyles. John Richards even patented a modern, treadmill-like "dog exercising device" for apartment dwellers in 1939. So, the stage was set for Dr. Robert A. Bruce.

Dubbed The Father of Exercise Cardiology, Dr. Bruce, a cardiologist and researcher at the University of Washington, took a Richards-style treadmill in the late 1940s and added an adjustable motor. In 1952, Dr. Bruce and his research partner, Wayne Quinton, unveiled the first motorized treadmill designed for medical use. This machine was used to diagnose heart and lung conditions via the now-famous Bruce Protocol cardiac stress test. Patients were hooked up to an ECG and put to work, with the speed and incline of the treadmill gradually increasing every few minutes.

This ability to accurately control and monitor the workload was the key. It enabled doctors to detect subtle changes in heart rhythms and precisely pinpoint defects, thereby eliminating the guesswork associated with previous tests. With the accessibility of a treadmill and the ability to control every variable, it’s easy to see how the Bruce Protocol instantly became the gold standard, recasting the bizarre, chaotic, and often-misguided history of the treadmill into a story of unquestionable medical triumph.

From Lab Test to Living Room Fad

The motorized treadmill, now recast as a life-saving medical device by Dr. Robert Bruce, was just getting started. In 1963, a seminal paper was published, detailing exactly how his treadmill stress test could be used to detect previous heart attacks, angina, or even a ventricular aneurysm. The Bruce Protocol had arrived, and variants of this test still form the basis of cardiac stress testing today. The days of diagnosing a heart condition only when the patient was flat on their back were officially over.

Enter another physician with a vision: Dr. Kenneth Cooper. Throughout the 1960s, Cooper had been an Army and Air Force physician, using treadmills to measure oxygen consumption and endurance in test pilots and those brave candidates for the space program. When he left the military, he brought that high-stakes testing to his Dallas clinic, running similar stress tests on regular, everyday patients. The results were shocking: he discovered hidden heart problems and, in many cases, ultimately saved lives.

His work, however, was wildly controversial. The medical community—the same one that had been relying on the ineffective Master’s two-step tests—thought Cooper was reckless. They considered the treadmill itself a danger to human health. “They thought we were going to kill people on the treadmill,” Cooper recalled. Instead, he simply proved that “the treadmill became a way to determine whether somebody is sick or is going to get sick.”

Cooper’s success in detecting heart disease led to an even bigger cultural shift. Already a runner, he believed that regular exercise—specifically, the kind that got you breathing hard and raised your heart rate—could prevent a heart attack altogether. In 1968, Cooper published a book outlining his plan. The title of the book (and the name of the movement) was Aerobics. And forget the Jazzercize and leg warmers that would follow—Cooper’s version was centered squarely on running.

Millions of ordinary people started pounding the pavement, boosted by Cooper’s book and by athletes who somehow made running cool. We’re talking about legends like mustachioed American long-distance runner Steve Prefontaine and Frank Shorter, who won the 1972 Olympic marathon gold.

One newly preoccupied runner was a mechanical engineer named Bill Staub. Staub was determined to run an eight-minute mile—a fitness benchmark Cooper had prescribed—but he faced a universal problem for runners outside of eternal summer: a wall of winter cold.

The medical treadmills in Cooper’s clinics were huge and expensive and were never intended for a New Jersey basement. Gyms themselves weren’t typical in the '60s and '70s, and the treadmills they did have were bulky and inconvenient, sapping the get-up-and-go simplicity that had made running so popular.

What Staub wanted was simple: to bring that convenience indoors. In his machine shop—a space previously dedicated to building fuel nozzles for jet engines, no less—he cleared room and built a basic prototype: two smooth wooden cylinders, a wide belt, and a motor with a simple on/off switch. This quickly developed into a production model featuring 40 steel rollers, an orange belt, and dials for setting the session time and speed. In a brilliant tribute to his inspiration, Staub named his company Aerobics Inc. His treadmill was the PaceMaster, and it sold in the late 1960s for $399 (a serious chunk of change, about $2,800 today).

"He was the pioneer for the use of the treadmill in the home,” Dr. Cooper confirmed years later. Staub’s genius creation, the world’s first mass-produced home treadmill, was an immediate success. The company was selling 2,000 units a year by the 1980s and had reached a momentous 35,000 units a year by the mid-1990s. Even after Staub's company folded in 2010, its closure was barely noticed in an industry it had helped create, which now includes dozens of companies competing in the single most popular exercise-machine category.

undefined

Polar H10

Heart Rate Sensor

When it comes to accuracy and connectivity, Polar H10 heart rate sensor is the go-to choice. Monitor your heart rate with maximum precision and connect your heart rate to a great variety of training devices with Bluetooth® and ANT+.

The Digital Age: Where the Treadmill Gets Smart

So, the motorized treadmill had already secured its place in history, conquering the doctor's office, saving countless lives, and, thanks to the likes of Bill Staub, successfully invading the American home. But what happens when a brilliant, life-changing design needs to evolve? It doesn't need to be replaced—it gets enhanced.

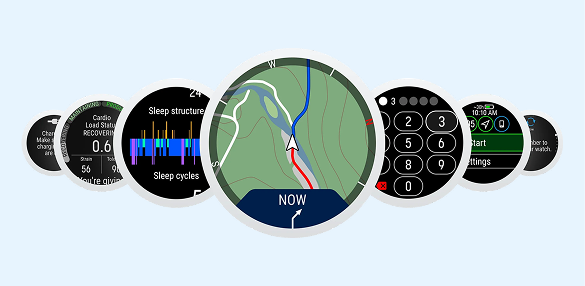

While the core mechanics (motor, belt, and frame) remain faithful to Staub's revolutionary PaceMaster, the most exciting advancements have been made in integrated technology, transforming a simple run into an immersive and highly optimized experience. The focus has decisively shifted toward making your essential cardio work smarter and more engaging.

Take the forward march of integrated technology, which in the early 90s began with features like shock absorption and quickly accelerated with the industry's focus on the user experience. By 2003, touchscreen consoles had been introduced, fundamentally transforming the running belt into a command center designed for maximum engagement and data synchronization. This spirit of innovation quickly brought us:

- Seamless smart device connectivity

- Built-in TVs (so you don't miss that episode while exercising/suffering)

- Virtual race experiences (so you can run the Boston Marathon in your basement)

- Custom exercise plans that adjust based on your stride length and cadence.

Beyond entertainment, innovation continues to tackle the fundamental act of running. Researchers at Ohio State University, for example, have devised a brilliant, if futuristic, solution to the classic user problem of constantly adjusting the speed dial. Using sonar technology, their prototype treadmill automatically detects your position on the belt and adjusts the speed accordingly—inching up if you move forward and slowing down if you lag. This ingenious development, which Associate Professor Steven Devor is working to bring to market, eliminates distractions and ensures a smooth, uninterrupted workout flow.

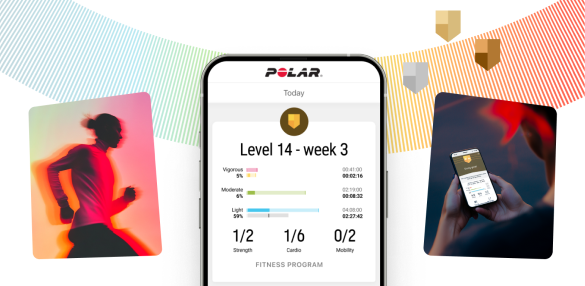

Crucially, this digital evolution complements the essential task of accurate performance tracking, a principle that Polar has always championed. Polar's dedication to precise heart rate and physiological data elevates the modern treadmill experience. By connecting seamlessly via Bluetooth® or ANT+ to a Polar heart rate sensor (like a Polar H10 chest strap or a wrist-based watch), you can wirelessly beam your real-time beats straight to the treadmill's computer. This enables the machine to utilize medical-grade accuracy for its own performance-driven programs, ensuring that the technology designed to save hearts (remember the Bruce Protocol?) is perfectly supported by the technology built to track them.

The treadmill has completed its chaotic, $1 billion-a-year transformation. Today, it stands as the single most popular exercise machine for both home and gym use, with nearly 53 million Americans relying on it annually and some 28.5 million considered 'core users' (logging about one session a week). It fulfills a serious and necessary purpose, helping to move bodies and save lives. The treadmill's history is a story of absurd twists matched with brilliant ingenuity, leaving us with a final, fascinating question: with all this innovative technology, are we finally starting to love the work?

Polar Vantage M3

Polar Vantage M3

Polar Grit X2 Pro Titan

Polar Grit X2 Pro Titan

Polar Grit X2 Pro

Polar Grit X2 Pro

Polar Grit X2

New

Polar Grit X2

New

Polar Vantage V3

Polar Vantage V3

Polar Ignite 3

Polar Ignite 3

Polar Ignite 3 Braided Yarn

Polar Ignite 3 Braided Yarn

Polar Pacer Pro

Polar Pacer Pro

Polar Pacer

Polar Pacer

Polar Unite

Grit X Series

Vantage Series

Pacer Series

Ignite Series

Polar Unite

Grit X Series

Vantage Series

Pacer Series

Ignite Series